Ohinemuri Regional History Journal 30, September 1986

(THE PAEROA-WAIHI GOLD EXTRACTION WORKS AT PAEROA)

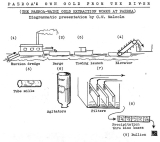

Diagrammatic presentation by C.W. Malcolm

For greater detailed explanation see:

JOURNAL No. 6 Page 43 by Cyril Gwilliam re precipitation [see Journal 6: Gold Mining in Karangahake - E]

JOURNAL No.11 Page 33 The Waihi-Paeroa Extraction Works by Roy Turner [see Journal 11: Waihi Paeroa Extraction Works - E]

JOURNAL No.21 Page 43 The Extraction of Gold and Silver by Gary Staples especially page 44, which deals clearly with the processes of dissolving the gold by the cyanide process, and its recovery by the use of zinc turnings and final refining [see Journal 21: - E].

The present article is merely a pictorial resumé such as was presented to school pupils in blackboard diagrams to give a simple explanation of what was an exciting local industry.

The Gold Extraction Works at Paeroa were approached either by Mill Road or from Junction Road. From Paeroa's original railway station where coal hoppers were situated near the present subway, a tram line ran along the edge of Junction Road turning off to the left not far from the Junction Wharf. Large coal trucks, drawn by horses, conveyed the coal to the river across which it was finally carried to the works by aerial buckets. Here too a footbridge gave access to the Works for the numerous workmen employed there and for us boys who ever found the place a fascinating rendezvous.

As other articles have recounted, much gold had escaped from upstream batteries in days before the cyanide process had been perfected. It lay in the silty tailings at the bottom of the Ohinemuri River waiting for the enterprising to recover it.

(1) By suction dredge, the silt was raised from the river bed, pumped into barges (2) and towed by launches (3) to the elevator (4) at the works. The stamps which were necessary to crush the quartz at the up-river mining batteries were not needed here as the material had already been thoroughly reduced. However, it was still further pulverised in the tube mills (5) whose rumbling could be heard in Paeroa as they constantly revolved with their contents of hard flints reducing the material to very fine proportions.

It was now the turn of the agitators (6), tall tanks some 80 feet in height. Here, constantly agitated by a current of air and by the addition of cyanide, the precious gold was actually dissolved. The muddy liquid was next introduced to tanks into which the large canvas filters were lowered. The liquid containing the dissolved gold was drawn into the bag-like filters and the silt remained outside to be discarded (7).

The process of recovering the dissolved gold has been fully explained in the fore-mentioned articles by passing the liquid through a series of boxes containing zinc turnings or filings to emerge in an unlikely looking state requiring the process of refining to produce the pure gold and other valuable minerals.

It was a sad day for Paeroa when, in 1918, this very large establishment closed down. There was no redundancy pay for the numerous body of experts and workmen. Figures given in the Diamond Jubilee Magazine of the Ohinemuri County Council, a valuable compilation by its then County Clerk, Mr Alf Jenkinson, tell us that 907,428 tons of material were dredged from the river and processed to produce 654,964 ounces of bullion, valued at 276,211 pounds ($552,422), and paying dividends amounting to over 18,000 pounds ($36,000). One would have to guess what these figures would be in today's terms. My own father's job working on the filters earned him the wage of eight shillings ($0.80) for an eight-hour day, with four hours on Saturday. If my memory serves me, and I believe it does, the men worked shifts as the process was continuous, except for a break around the Christmas period.

I feel that this exciting and valuable part of Paeroa's history is well worth at least a brief restatement from earlier articles to remind us of something that was very real in the life of the town almost seventy and more years ago.