KARANGAHAKE the years of the gold 1875 -1935

Before the opening of the Ohinemuri Goldfields there can have been very little settlement at Karangahake, the hilly district, to a considerable extent being covered with bush. It came right down to the banks of the rivers, and according to early surveyors, the forest primeval shadowed the nucleus of what was to be come a township.

Our story must involve two races, the Maoris whose ancestral land this is, and the Europeans who ventured here. It will be the story of Rivers that were arteries sustaining life though destined for a time to become veins of pollution; of Forests that were sacrificed, and of a Mountain that required the most arduous labour to make it yield its rich abundance. Most of all it will be the story of the People who lived in this district during the first 50 years or so of goldmining.

It is the golden background that gives the history of the area that flavour of romance, that makes it at once lively and unique. The Ohinemuri Goldfields were different in character from other New Zealand fields and its extensive "Underground" was a brief world of wealth coupled with stark realities, great dangers, and for many of the miners, meagre rewards. Considerable Capital was needed for development, and often this came from overseas whence dividends returned.

About 100 years ago (in the l870-l880s) New Zealand was suffering from an acute depression, although ship loads of would-be settlers continued to arrive at ports with no guarantee of work to provide a living. It would be true to say that their situation was desperate and they were willing to explore the hinterland in search of a solution. Many of these men had worked the Coromandel Field (opened in 1852) or had become redundant after a few productive years on the Thames Goldfield which opened in 1867. The Waihou River provided a wonderful highway towards a possible "Eldorado", where, it was rumoured, gold had been located.

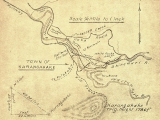

The Ohinemuri River, rising near the East Coast of the Coromandel Peninsula, flows westward, cuts through the main range between the fault-riven cliffs of Karangahake Gorge, to be joined by the turbulent Waitawheta which flows between the Taukani Hill and the Karangahake Peak, 1786 feet high. Then, with rapidly flattening grade, it winds its way to join the Waihou, a little beyond Paeroa. For some fifty years after 1875, the mountain, its spurs and adjacent hills were to yield much gold and silver, causing the rise of a town with a population of around 2000 by 1907. But headway was lost, gold mining petered out, and by 1920, buildings were following people out of Karangahake. The imposing peak was left riddled from near the top to below river level, while above ground nearly all evidence of great installations and a crowded town, were gone.James Mackay, Government Land Purchaser, a skilled and astute negotiator, again proved very accommodating with food and other supplies while the matter was being debated at length.

In August 1874 there was a very big meeting at Whakatiwai, (near Miranda), when it was estimated that 3000 Maoris again discussed matters with the Europeans who arrived from Thames by the steamers Enterprise and Ventura. It then became apparent that there would be no further obstruction to the opening of the field after the signing of the Deed of Cession the following year.

By 1875 it was estimated that there were about 400 Europeans camped in the vicinity of Paeroa and a number of stores were plying their trade there, while Mr Lipsey and others were busy packing their goods nearer to the "Gorge".