Ohinemuri Regional History Journal 28, September 1984

BY C.W. MALCOLM

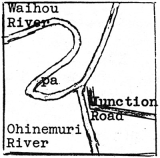

Paeroa's Junction Road, so named because it ran from the township to the point where the Ohinemuri and Waihou Rivers met, was once a busy highway of commerce and passenger traffic. In 1896 the Auckland Weekly News reported that the road was used by "64 carriers and their 164 horses" who would be out of work unless urgent metalling was undertaken. In those days "the Junction" was a busy river port for the district.

But now, in 1984, where the Waihou made its great sweep to join the Ohinemuri, new interest centres on the area where, long before the European settlers came, a Maori village nestled within the encircling curve of the river. The Rev. Samuel Marsden spent a Sunday with these first Paeroa people, it was the 18th June, 1820. Today extensive excavations being carried out have revealed ancient artefacts that take us back in time to the lives of these early inhabitants.

Long before this historic uncovering of the past, hundreds of the school pupils I taught in Paeroa, Netherton and elsewhere had their interest stimulated by a very small collection of artefacts which has since been donated to the Historical Society's Museum in Paeroa. In studying them, these pupils gained an appreciation of the ingenuity and patience of the ancient Maori people who fashioned them. It is one thing to look at a large collection of Maori artefacts, it is quite another to see and handle with awe and respect a few of these ancient relics.

Most of this small but typical collection were recovered from the mud of the river, miraculously preserved, by the "drag-line" building the stopbanks, seen by the watchful eye of the operator, snatched from destruction, and thoughtfully presented to me for use in my teaching. Evidently his children had carried home some of my enthusiasm for the history of the district. He was the late Mr. Harry Wilton, Gallipoli veteran, and a fellow officer in the Paeroa Volunteer Fire Brigade.

A dozen or so stone adzes are more or less common finds but the lesson they teach us in this age of technology is one of infinite patience - the patience of uncounted hours and painstaking toil to shape them and give them their smooth finish and sharp cutting edges.

Stone endures, indefinitely, but consider this wooden implement: a mere stick about 20 inches long, one end shaped to resemble a narrow trowel, the other worn round and smooth by the hand of a Maori maiden who employed it to weed the kumera patch. It never ceased to fascinate me as I held it in my hand, conscious of the brown hands that once grasped it and toiled with it among the kumera, possibly on that pa within the bend of the old Waihou. I parted with it reluctantly but feeling it would appeal to a wider range of viewers, surrendered it to the Museum.

But that cracked and broken remnant of a canoe-bailer really captures the imagination. It could easily be passed by as a mere gnarled piece of flotsam dredged up by chance from the river silt. How long must it have lain there, lost from a canoe on the Ohinemuri a couple of hundred years ago? The sides of the "scoop" have gone but there are still evidences of the careful shaping necessary in the making of an instrument that will efficiently scoop surplus water from an overloaded canoe. And the central handle is still there - at least a good part of it. No maiden's hand grasped this stout handle; as my fingers closed round it I was conscious of the strong grip of some intrepid warrior on his canoe upon the surface of the Waihou or Ohinemuri long before he had ever seen a white man.

A woman's hand, however, must surely have worn smooth the well-preserved wooden fern-root pounder with which the root of the abundant bracken was prepared for eating. Dug in summer, and dried in its heat, it was a constant source of food that never failed whatever the seasonal conditions. Stored until needed, it was roasted on hot embers and then pounded on a flat stone. The resulting moist and glutinous part was extracted by the process of sucking and the fibrous remainder spat out. The taste is said to have resembled that of the crust of newly-baked bread and was very nourishing. Indeed Bishop Selwyn declared he found it the best kind of food to eat during his long walking tours. My pupils, seeing the "pounder" for the first time, would raise it with mock gesture of defiance, imagining its use as a club; to be somewhat deflated on learning that, in spite of its appearance, it was no implement of war but the most important "kitchen utensil" used by the ancient Maori housewife!

With what patience did the Maori sit on the banks of our river waiting for a bite that would provide his next fish meal, his line held in the depths by its cleverly shaped stone sinker. You see the grooving made to hold the flax line secure to prevent its slipping with the consequent loss of the cunningly and laboriously made sinker.

And what is this other stone article, cylindrical in shape and tapered to a point? Elsdon Best in my copy of the "Maori As He Was" illustrates similar objects which are actually the toys of the Maori boy - "whip tops" and even "humming tops". So when in the school playground, "tops were in," it was not the European who first spun his tops in Paeroa!

I liked to think that, among my small collection of artefacts, there was one that long, long ago, in or near my boyhood home of Paeroa, occupied the centre of a ring of gleeful, laughing boys and girls of a splendid race that had not yet seen a white man.

I subscribe this article as a record of the value of my small collection of "Maori relics" from my home district, a collection that has enlivened my teaching of Maori history for hundreds of young people over some 40 years, in the hope that as they are seen among a larger collection of artefacts, they may stimulate deep thought and appreciation of the history they have to tell.